It’s the middle of May, the morning sun slices through the clear blue sky as if systematically rotated into place just after a full moon and a week of unpredictable rain. A small fleet of boats set out across the Chesapeake Bay, united in their purpose. Each vessel houses an assortment of volunteers consisting of scientists and passionate citizens, a group that could very well be in the process of marking the first step to determining a true population assessment and distribution of one Maryland’s most iconic species, the Diamondback Terrapin.

It’s the middle of May, the morning sun slices through the clear blue sky as if systematically rotated into place just after a full moon and a week of unpredictable rain. A small fleet of boats set out across the Chesapeake Bay, united in their purpose. Each vessel houses an assortment of volunteers consisting of scientists and passionate citizens, a group that could very well be in the process of marking the first step to determining a true population assessment and distribution of one Maryland’s most iconic species, the Diamondback Terrapin.

As Maryland’s state reptile and university mascot, these turtles exemplify our struggle with the “Great Shellfish Bay” and how to find a balance between enjoying its vast resources and protecting it from ourselves. Terrapins have received a lot of abuse over the years, from being exploited for its meat to the ever expanding issue of nesting beach destruction. The Maryland Terrapin Working Group was created to drive the enacting of the commercial harvest ban and has continued in its efforts so terrapins can be saved from additional threats. One of the first steps has been to obtain more data so we can figure out where the population stands today and what areas are most critical to their survival.

My contribution to this ambitious task was to volunteer as a citizen scientist representing the Mid-Atlantic Turtle & Tortoise Society (MATTS) and my newly formed wildlife group, Susquehannock Wildlife Society (SWS). I was asked to survey alongside Scott Smith, a wildlife biologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Paula Henry, Research Physiologist at the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, and Chris Todd, fellow founder of SWS and DNR Park Ranger at Rocks and Susquehanna State Park. We split up the workload, having one person drive the boat, another record the data, and one designated spotter in addition to all other roles also searching. The bay is huge place with a ton of ground to cover and having only a handful of folks to do it makes it even more difficult. With any daunting project, you have to start somewhere and when asked where my team should focus our efforts I could only think of one place, the Wye River.

My contribution to this ambitious task was to volunteer as a citizen scientist representing the Mid-Atlantic Turtle & Tortoise Society (MATTS) and my newly formed wildlife group, Susquehannock Wildlife Society (SWS). I was asked to survey alongside Scott Smith, a wildlife biologist with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Paula Henry, Research Physiologist at the USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, and Chris Todd, fellow founder of SWS and DNR Park Ranger at Rocks and Susquehanna State Park. We split up the workload, having one person drive the boat, another record the data, and one designated spotter in addition to all other roles also searching. The bay is huge place with a ton of ground to cover and having only a handful of folks to do it makes it even more difficult. With any daunting project, you have to start somewhere and when asked where my team should focus our efforts I could only think of one place, the Wye River.

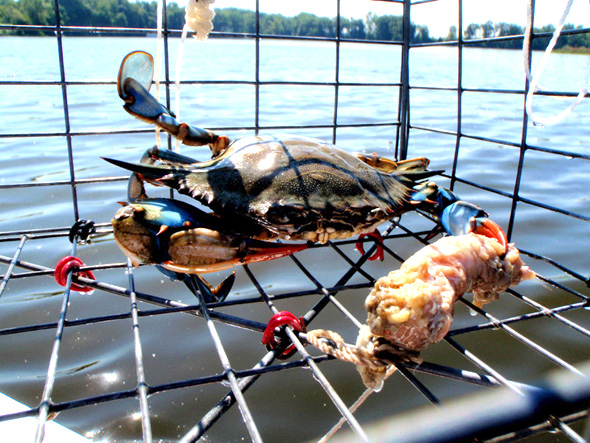

The drive to Wye Mills is one I could do with my eyes closed. I had frequented this mighty tributary of the bay several times a year since before I could probably even say the word “turtle”. It wasn’t terrapins, the largest white oak, or even the incredible scenic beauty of this place that has drawn generations of my family here. It was the blue crabs. Arguably the largest, heaviest, and deepest blue colored examples of these tasty crustaceans you will ever find. None of us ever fished for a living. We were merely “chicken neckers”, recreational crabbers who would use collapsible traps connected to a homemade float with rope connecting the two. When I was a little kid I remember waking up at 3:00am to begrudgingly head down to the river with my dad and grandpa, too young to have a true appreciation for things steamed with spicy Old Bay and beer. Being practically raised in the great outdoors I could never complain about spending time out on the water, even with a sometimes overwhelming workload as we fought to harvest our bushel basket treasure. It didn’t take long before I found a magnetic force of my own to drive me to the Wye, one that was most certainly to become an annoyance for those seeking a bounty of crabs.

My elementary school obsession with turtles had begun and while the painted, box, and snapping turtles of my suburban neighborhood were cool, there was a species that had a worn out page in my Petterson and Golden field guides. The diamondback terrapin fascinated me because it could display such incredible markings and was specialized for a brackish water habitat; eating the crabs, snails, and clams found there. Once I knew what to look for, I started seeing the little smiling heads peering out of the water at us as we would travel for one crab pot to another. One glorious day the bycatch found in one of our traps turned out not to be a horseshoe crab or catfish, but a terrapin! I was amazed at the size of this beautiful female and the fact that she was able to squeeze into a twelve inch aluminum cage. After that point terrapins were all I wanted to see on the river and became a distraction from my contribution to the family feast. Some people fondly remember getting a bike they had always wanted, their first crush, or even their high school graduation. For me however, some of my favorite and most vivid memories are seeing a turtle species in the wild for the first time.

Some twenty years later, this lovely spring day would not be the first time I had seen terrapins but it would be the first time I was searching for them with a purpose other than my own personal enjoyment. This transition is significant for me and a theme that I been fortunate to have enjoyed over the last several years as a largely self-educated wildlife enthusiast. My career and degree don’t point anywhere near the direction I have found myself today but here I am, sitting alongside incredible experts, who with open arms have allowed me to assist them in their efforts and help make a difference with species I have been so passionate about throughout my life.

Hoping that I didn’t steer these good folks wrong in selecting this particular survey area we head out into my old crabbing grounds. We set our GPS starting point and start scanning the water surface and shoreline for bobbing heads with that unmistakable black or white mustache that most terrapins wear in an almost comical fashion. We cruise slow and pull out our binoculars. After a few false alarms from floating white leaves and debris, we quickly confirm a sighting. Personally I was ecstatic that we didn’t get skunked since a few times I had come out to the Wye and not seen any terrapins. We stop and take notes in the predetermined fashion our group had agreed upon- GPS location, distance from shore, habitat characteristics, weather conditions, tide, and sex of the individual if possible. Terrapins are sexually dimorphic with the females being much larger with huge heads in comparison to the males. Young females are difficult to determine but most of the time you can make a call depending if you see a large or small head and the overall carapace (upper shell) length.

We move further up the river, following the contoured shoreline into various cuts and coves. We start seeing more and more terrapins to the point that it is becoming difficult to count them. Call us pessimistic but we had never expected this kind of turn out. Apparently instinct was running strong and this area was a suitable place to get together for their ritual breeding activities. Multiple turtles were basking on fallen trees and at times, dozens of heads and even shells floating above the surface as they attempt to bask from within the safety of the water. On a few occasions we counted over thirty in one scan and confirmed this number with all four of us acting as spotters.

The variation of coloration and markings for one turtle species in a single area is fantastic. There are individuals that have shells that are almost jet black with skin that has tiny speckles of white and gray. There are others that have white skin with black blotches and light shells that have the black concentric circles that look almost as if someone had painted them on. Others display a mix of the two. I have heard stories that after terrapin numbers dropped and turtle soup lost its popularity in the early twentieth century a lot of the terrapin farms released an assortment of turtles that could very well have represented several of the subspecies found to the south. One could conclude that the “Chesapeake phase” as some call it could be a hybrid of several others. It’s an interesting theory but one I suppose we may never prove to be true.

The Wye River held many other treasures for us along the way. We were almost instantly greeted by a bald eagle and several ospreys soaring above us. There were quick glimpses of sting rays and an endangered Delmarva fox squirrel. Kingfishers and two species of heron stalked the shoreline for a fish lunch. We had a muskrat that we had almost mistaken for a river otter at first because of its size. Perhaps most unexpected was the immense population of northern water snakes. Not uncommon by any means but there seemed to be one skidding across the surface at every turn. We were also treated to getting to observe a gutsy raccoon venture out into the daylight to forage along the bank, hopefully he won’t be one of those who learn that terrapin eggs make a nice little snack.

After about three hours of searching we found a good location to end the first portion of the survey. The guidelines we set were to count everything we could and then perform another count along the same route heading back towards the starting point. The combination of these two sets of data has shown in other areas to represent a fairly accurate assessment of that population. We retraced our path and even though the day continued to heat up we kept observing the same groupings of turtles. We constantly scanned in different directions and verified most of the sightings with at least two of us if not all four. In total we counted one hundred and thirty individuals in each direction. This is an impressive quantity to find of any reptile in a limited area and a group that could very well sustain itself forever if provided adequate nesting areas and protection.

We eventually crossed back over our starting point and sighed with relief that not only did our survey techniques prove to be successful but there was still what appeared to be a very healthy population of terrapins here in the Wye. Things may not be as bleak as we had feared. We know that not all areas will show these kinds of results but it appears that with a little fine tuning we may now have a tool to give us the data we need to move forward with a plan for their protection. We hope to expand our efforts and get a true snapshot of terrapins in our state and nationally. Now is the time to begin shaping up a conservation plan to protect and enable growth in our Chesapeake terrapin populations so future generations of crabbers and wildlife admirers can enjoy these diamonds of the Wye.