You may remember hearing about a wayward manatee that meandered its way to the mouth of the Susquehanna just a few years ago. While a manatee is always a pleasant surprise, we now have a new Florida species that has found its way to our shores. On February 1st, a family with waterfront property along the Bush River contacted the Mid-Atlantic Turtle & Tortoise Society (MATTS) about an unusual guest on the beach behind their home. This creature was about fifteen inches long with a snorkel-like nose and a large flat leathery shell. This was not something out of a science fiction story but a Florida softshell turtle. Harford County does not have any native softshell turtles and the closest related species is the Eastern spiny softshell which is extremely rare in Maryland and has last been recorded many miles away in Garrett County. That species is listed as “In Need of Conservation” by Maryland DNR.

You may remember hearing about a wayward manatee that meandered its way to the mouth of the Susquehanna just a few years ago. While a manatee is always a pleasant surprise, we now have a new Florida species that has found its way to our shores. On February 1st, a family with waterfront property along the Bush River contacted the Mid-Atlantic Turtle & Tortoise Society (MATTS) about an unusual guest on the beach behind their home. This creature was about fifteen inches long with a snorkel-like nose and a large flat leathery shell. This was not something out of a science fiction story but a Florida softshell turtle. Harford County does not have any native softshell turtles and the closest related species is the Eastern spiny softshell which is extremely rare in Maryland and has last been recorded many miles away in Garrett County. That species is listed as “In Need of Conservation” by Maryland DNR.

So how did this turtle find its way here in the upper Chesapeake watershed? What we know for sure is that someone released the turtle here. Softshell turtles are a common species in Asian food markets and it is possible that a well- intentioned citizen tried to “rescue” this turtle by releasing it in this non-native habitat which it is not adapted to survive. The other possibility is that it was a former pet that was no longer wanted. It is quite common with reptiles and especially turtles for people to buy on impulse a cute quarter-sized baby turtle at a pet store, reptile show, or from a novelty shop at the beach. What they don’t consider is that the cute baby turtle would live for over forty years and grow larger than a dinner plate. This causes people to “let them free” and “return them to the wild” but they don’t realize they are doing more harm than good.

Species like the red-eared slider, a very popular pet species from the central and southern United States, are now established and breeding in many areas of Maryland and elsewhere around the world. Large non-native species like the slider could possibly overtake the limited food and basking areas once reserved for our native turtles. Reptiles also have special needs that most casual pet owners are unaware of. Turtles require special lighting, clean water, a lot of space, and a balanced diet that mimics their natural food sources. A pet turtle thrust into a natural environment it has never seen also stands less chance of surviving and can spread diseases to native species. The softshell turtle that was found was covered in sores and had swallowed a fish hook while trying to find food. Foreign turtles can carry diseases that our native turtles are not yet immune to. Even removing a native turtle like a box turtle from the wild, keeping it with a store bought non-native turtle and releasing it back into the wild can cause a potential threat to entire populations. This only furthers the argument that pets are meant to stay as pets and wildlife needs to remain wild!

During the first two years of the Maryland Amphibian and Reptile Atlas (MARA) project that is sponsored by Maryland DNR and the Natural History Society, many non-native and potentially invasive species have been discovered. Although most exotic species can’t survive our winters, during the warmer months several boa constrictors and pythons were encountered in a number of areas. In places these large predatory snakes can survive, such as the Florida Everglades, are now plagued with them and creating havoc on the native wildlife populations. Locally, geckos and anoles have been seen, perhaps stowed away in an imported plant. Lost or released pet tortoises have been found wandering around suburban areas.

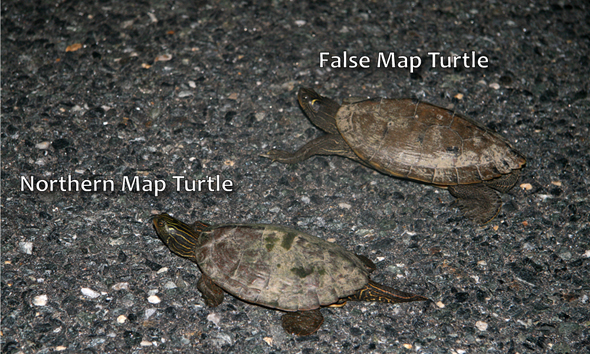

False map turtles, usually found in the mid-west have been observed in Howard and Harford Counties. In Howard a female was discovered laying eggs and in Harford there is perhaps a greater threat since they are capable of interbreeding with the native endangered northern map turtle. Species that can interbreed with our native populations cause a potentially greater risk than others because the genetic integrity of our wildlife could be lost, essentially creating a new species.

Everywhere we look we see reminders of just how dangerous the importation of foreign species is to our ecosystems. Think about the enormous flocks of chattering birds that often fill the sky and tree tops. The one that most likely comes to mind are European starlings, a species introduced into New York’s Central Park and adapted so quickly that it now more common than most of our native birds. Deemed an environmental disaster, they destroy crops, cause danger to air travel, displace native birds, not to mention the damage to our structures and the cost to clean or repair. Another classic example is the pigeons that we associate with most urban areas (actually called rock doves) that originated in the eastern continents. Think about the stinkbugs annoy us, the snakehead fish that give us nightmares, mute swans which appear to be an elegant addition to a pond but destroy aquatic vegetation, emerald ash borers that threaten our trees, the phragmites that choke our wetlands, and the zebra mussels that hitchhike on our boats. Many people don’t realize that carp and pheasant are actually European and Asian species that had been long ago introduced for the purpose of being harvested for food. The ecosystem we see today is much different than that which the Native Americans knew before European settlers arrived.

These are things to consider. Our harmless and usually well intentioned actions can have a major impact. We are grateful for families like the one that discovered the softshell turtle. Instead of returning it to the wild, they recognized that something was unusual about it and contacted the proper group to provide information on what to do. One of the services the Susquehannock Wildlife Society provides is to consult on local wildlife matters and to many times act as a resource that can help rescue and transport wildlife to local veterinarians and/or rehabilitators. We cannot do this alone, however. We rely heavily on everyone in our community to help us with transportation, look out for wildlife, and keep us informed of wildlife in need. We are always interested in reports of unusual species (including escaped pets) and even seemingly common sightings that we can use to assist in future conservation and research efforts such as the amphibian and reptile atlas we are currently participating in. Together we can make a difference to protect our wildlife, even if it means helping to prevent the spread of nature’s unwanted guests.

Below is a list of resources:

– Found wildlife in need of rescue or identification?

Call our wildlife hotline 443-333-WILD or email us at contact@suskywildlife.org

– Need more information on invasive species and how you can help identify them? Visit the Maryland Department of Natural Resources invasive species page

http://www.dnr.state.md.us/invasives/

– Want to help us with our statewide reptile and amphibian atlas? A simple digital photo with the date and location of species found (even common ones) is a great help to us! https://www.susquehannockwildlife.org/projects/maryland-amphibian-reptile-atlas/

– Unwanted Pet Turtle? Don’t release it into the wild, contact MATTS at http://www.midatlanticturtles.org/adoptions.html