After a late summer, the true feel of autumn had begun to set in throughout the Mid-Atlantic. As with every year, nature painted its glowing mural through the treetops like a wildfire that calmly cascades along the roadways, river valleys, and distant hillsides. During this time, wildlife works diligently to prepare for the cold season ahead, gathering food, teaching their young how to evade starved predators, and seeking shelter until the harsh weather passes and the life-giving warmth of spring returns.

We all think of turkey dinners, falling acorns, colorful leaves, hot apple cider, and pumpkins when fall comes around. Few of us associate this season with migrating timber rattlesnakes that meander back up mountainsides to find refuge from winter temperatures deep inside rock crevices. This ancient event is one that most folks have never seen and with populations continuing to decline, may never be able to in many locations.

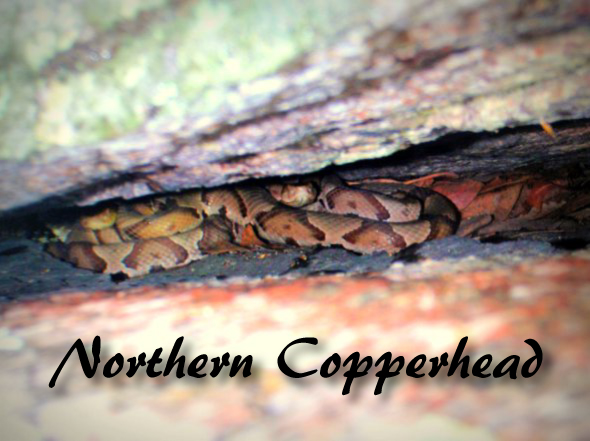

As with the majority of people east of the Appalachians in the Northeast, I live in an area where credible reports of rattlesnakes haven’t been recorded for probably over a century. Ever since I was a kid I longed to see these misunderstood creatures, a symbol of untamed American wilderness, in their natural habitat. Surprisingly they can still be found, although in low numbers, within a short distance of Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and New York City. In Maryland, we only have two venomous snakes- the northern copperhead and timber rattlesnake.

Another species, the cottonmouth, or “water moccasin”, commonly misidentified and confused with the non-venomous northern watersnake, is NOT native to Maryland and found from southeast Virginia and further south and west.

Copperheads are also confused with watersnakes, milksnakes, and several other boldly patterned snakes. If you can’t identify a snake, leave it alone. If you are sure it is a venomous snake and need it removed, the same applies but your best option is to call a professional that can do so. Snakes are critical components of the ecosystem and should not be killed. Despite what most people think and while widespread in their distribution, even copperheads are relatively uncommon in most areas. Where present they are typically in areas where there are wooded hillsides, rock outcroppings, and often near a water source where they can hunt for amphibians and small mammals. Many snakes have unnecessarily died by the blade of a shovel out of fear because they were misidentified and thought to be a danger. Snakes are just another wild creature struggling to survive. They have no evil intent and a world without them is one we cannot afford to experiment with.

Rattlesnakes have been targeted perhaps more than any other. They are only found only in the Americas and have one major characteristic that sets them apart from any other species. Several types of snakes, venomous and non-venomous, rattle their tails when trying to ward off a potential threat. Only the rattlesnake has the iconic scale segments at the end of its tail that when vibrated together rapidly sound a warning to those who would prey upon or accidentally step on them. This great defense is exactly that; these snakes do not aggressively seek to strike creatures that it does not require for food. Built for stealth and camouflaged to match its surroundings, it is particularly kind that it gives audible notice of its presence since they are easily overlooked. After that, it’s fair game if an unfortunate animal continues to advance towards it. They can cause a painful bite, but the venom of timber rattlesnakes at least would not prove deadly to most as long as medical attention is sought.

I have a fair knowledge of how reptile habitat and behavior, but snakes and particularly rattlesnakes can be difficult to find if you don’t know what you are doing. With a species that has been intentionally exterminated in most of its historic range, it becomes increasingly difficult because even though the landscape fits the needs of the species it doesn’t mean they are still there. They are certainly a needle in a haystack if you are trying to find them in the open forest, but having a documented den site to search makes the job much easier. So that I didn’t have to drive a few hours and hike all over the mountains only to not find any snakes, I set out to determine who was researching rattlesnakes in the region and would have the most working knowledge of their locations and ecology.

All of my sources pointed towards a man who has been trekking up and down the Appalachians for decades studying timber rattlesnake populations, a man named William H. Martin, or “Marty” as he prefers to be called. I contacted Marty, who gladly accepted my request to tag along on one of his research outings and take photos while trying to help count rattlesnakes at one of the den sites, or hibernaculum (place where they hibernate). There were only two conditions to going on the survey: follow his instructions to ensure my safety and I couldn’t tell anybody about the location of the snakes. They are protected by law in most states so this is confidentiality is required. The reason for this is because of the sensitive nature of these sites where rattlesnakes give birth and hibernate, the goal is to keep away humans that would potentially kill, collect, be injured by, or disturb the remaining few individuals at these very special places. Since they have a slow reproductive rate, even just a few snakes, especially a female of breeding age, being removed from a site could collapse the whole population.

I headed out west, past the hustle and bustle of the Baltimore beltway system, enjoying through my windshield the view of the ancient Appalachian Mountains, which slowly rise from the horizon as the miles roll behind me. As promised and for the protection of the animals, the exact area we explored will remain undisclosed and from here on out I will refer to it as “Rattlesnake Mountain.” The landscape of this place could be found in eastern West Virginia, Northern Virginia, Southwestern Pennsylvania, or Western Maryland. Once having met the search crew, which consisted of Marty and another wildlife enthusiast named Zach Orr from North Carolina, we headed to the spot where the snakes were known to gather in decent numbers. As we drove, Marty pointed out various spots along the ridges where only a few snakes were still found, some spots where none were found, one where copperheads were more prevalent, one where timber rattlesnakes were, and some where both could be found. The den site we were heading to was one that both species used.

It was a cool, overcast day with a fairly strong wind blowing. Not exactly “snake weather,” but our guide felt that given that the snakes instinctively gather around the den site at this time of the year (give or take a week or two) we would still have a chance at seeing some. Weather plays a large part in the behavior of snakes and is one of the elements Marty documents to correlate population fluctuations. As we hiked up the switchback trail that would lead us over the ridge to the sun exposed rocky side of the mountain, I quickly observed that Marty must be part mountain goat, part human. Being twice my age he easily outpaced me, someone whose endurance is limited more to the subtle hills of the Piedmont and coastal plain, not to mention that I was, as always, lugging an assortment of photographic and video equipment. He was outfitted like a true wilderness adventurer, having a pocketed utility vest and carrying only a small pack with a snake hook and journal for recording his findings. It was clear that he was well acclimated to this terrain from decades of doing this work.

We continued through the forest on the ridge after leaving the trail and arrived at an area that I instantly recognized could yield rattlesnakes. There were large rock outcroppings and sections of rock slide with plenty of places to hide and hunt, not to mention the open canopy which would allow sufficient basking. Here were all the makings of good snake habitat. It was time to start actively searching. With the cooler weather and cloud cover it was unlikely we would see snakes out on the ledges. Instead, Marty showed us how to look deep into the rock crevices even though most seemed like you could barely fit your hand inside of them, let alone a thick-bodied snake that could grows up to five feet long. We continued to climb, jump, and balance from one boulder pile to another. As we squinted our eyes and shone our flashlights into the deep cracks, Marty would explain various facts about the natural history and ecology of these fascinating snakes. Some information one could possibly find if you sat in a library for the day with a stack of herpetology text books and some stemmed from decades of real world research and observations.

Being a lifelong student, I ate up all of the amazing insight derived from Marty’s lifelong pursuit. I asked if the snakes were typically heard first or were more often seen before they would rattle. Oddly enough, most of the timber rattlesnakes in this region don’t usually rattle. I would not have expected to hear this, but the theory presented makes sense if you look at it from an evolutionary perspective. The rattlesnakes that were historically more predisposed to rattle would be the easiest to locate and therefore kill during the horrific roundups that used to occur here and still do in other parts of the country. With all of the large mammals such as elk and bison now absent from the forests, the snakes also don’t have the need to warn animals that could potentially step on them. The snakes that survived the roundups were likely the ones that didn’t rattle and were better at hiding. Those snakes continued to breed until today when those traits were passed down through their genetics, resulting in a loss of this once built-in reflex. These were very interesting ideas to consider.

I asked how these snakes knew to come to these locations every year. The snakes not only hibernate in these locations, but females give live birth to the young, eggs are not laid like many snakes. This allows them to imprint on the site so they know to come back to it after the summers were they fan out across the lower areas of the mountain to hunt for food. They may travel a large distance away during this time but if the odds play in their favor, year after year they will find their back. When humans move snakes from these areas to others or their dens get destroyed, their rate of survival decreases significantly. This furthers the need to protect the sites that are being used.

Another question was how these snakes could be found in coastal areas further south, even being nicknamed “Canebrake rattlesnakes,” but throughout the northeast in similar lowland areas they no longer survive. All evidence points to them now being banished to the higher elevation areas because, frankly, they were killed whenever people found them, until the populations disappeared. Because they gather in den sites, they were easy to wipe out in large numbers once found. That makes sense but what about the areas in those higher elevations that appear to have good habitat but are vacant of rattlesnakes? One of the problems these snakes have even in protected areas where humans leave them alone is trees. Trees are good, right? The more the better? Well, not always, and especially not because their canopy that could affect the viability of rattlesnake dens. Snakes depend greatly on an abundance of direct sunshine to thermoregulate, or raise their temperature, while basking. This is required for digesting their food as well as the development their young prior to birth. Once the tree cover grows too thick, it shades the rock outcropping and cools it down enough that the snakes will no longer thrive and over time will fade away as breeding and long-term survival decreases. With the suppression of fire, usually caused by lightning strikes, for the safety of residents around the parklands and wild areas where the snakes are found it means that trees can grow wherever they are able.

We also got to hear stories about the other wildlife that one could encounter in these remote regions of Rattlesnake Mountain. Marty had seen black bear in the area, higher numbers of the sometimes arboreal gray fox than red foxes, and one time was even startled by a bobcat as it leapt out from where it was hiding beneath one of the rock ledges. Other snakes often share the dens of timber rattlesnakes. As mentioned earlier, copperheads were usually found around the timber rattlesnakes, displaying the same hiding behavior and utilizing the same dens.

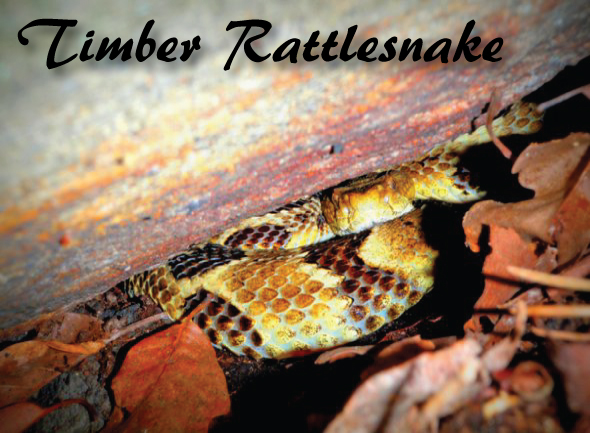

Suddenly, Marty stopped in mid-sentence and nonchalantly said, “there’s one,” while immediately stepping away and pulling out his field journal to record his observation. He pointed to the rock where the snake was hiding. Boy, was it hiding. At first I couldn’t make it out, but, sure enough, sandwiched deep between two flat rocks was the unmistakable scaled skin with yellowish coloration and dark alternating bands that I was hoping to see. Even though I could only see a portion of the snake, it was exhilarating. I snapped a few shots with some degree of difficulty since there wasn’t much light and, frankly, not much to photograph, then moved on to hopefully find more. We all shared the same ethics when it came to wildlife. There was no need to disturb the snake and remove it from its hiding place like some would do without purpose other than seeing the full body of the snake. Since we weren’t there to mark, tag, or weigh the snake, the simple record of its presence was enough and would save having to add any additional stress to this creature just prior to its winter rest.

Soon we would encounter more snakes wedged in a similar fashion; some were more and others less viewable to us. In the back of my head my imagination kept me envisioning nearly stepping on the snakes everywhere as I stumbled and tripped over the awkward rock piles, but all of them on this day were neatly tucked away. We did find one individual that was more out in the open as we began to climb back up the hillside. This one was a really nice black phase with very dark markings. We got close – due to the cold weather it paid us little mind – but, even in its resting state it continued to flicker its tongue at us, gathering information to determine the level of threat.

We did not find any copperheads on this particular trip, but I felt fortunate to find five timber rattlesnakes despite the unfavorable weather conditions. The company, newfound knowledge, and getting to experience this amazing habitat with one of our most amazing native species was something I would never forget. While standing out on the ledge at the top of the rock slide, through a clearing I looked out across the valley below and imagined this land as it once was, vast, wild, and free. I felt that despite all odds, and all of the destruction we have caused, that there is still hope and that it isn’t too late. We can still protect those species that remain and give them a real chance to bounce back. If we open our minds and hearts to understanding that everything from the bald eagle soaring through clear blue skies, to the black bear lumbering through a patch of blackberries along a roadside, to the rattlesnake resting on rocky ledge with its recently born young crowding around it for warmth, deserves a chance to flourish as they once had. Despite our fears and desire to modernize the world around us to suit our needs, we hold the power to change course. We owe it to our future generations who should have these icons of America intact to enjoy and admire. I hope that one day, my tale of “Rattlesnake Mountain” could take place just about anywhere.

*Photos by Scott McDaniel