New Research Published on The Effects of Road Mortality on a Spotted Turtle Population by Susquehannock Wildlife Society

Many different types of wildlife around the globe are facing increasing pressure from development and loss of native habitat as human populations continue to expand. One of the most pressing issues facing wildlife populations is the broad-reaching direct and indirect effects that roads have on them. Roads prevent wildlife from moving from one habitat patch to another, change animal behavior, and most devastatingly often lead to animals getting hit and killed by vehicles. The Susquehannock Wildlife Society in collaboration with Towson University has just published a new study investigating the impact that road mortality has on a population of Spotted Turtles in Central MD.

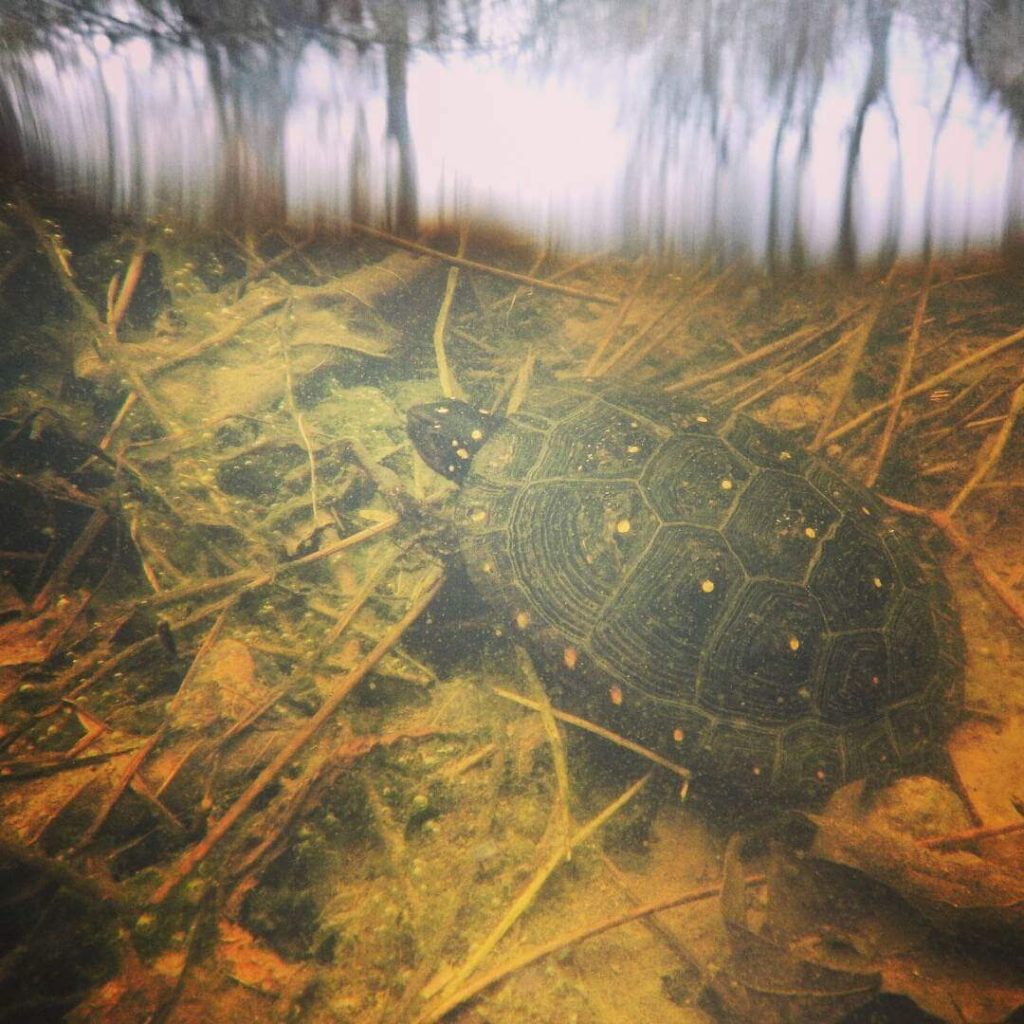

Spotted turtles are beautiful black turtles speckled with bright yellow spots. The small turtle is found in various wetland ecosystems across the Eastern seaboard from Ontario down to central Florida. This new study shows that a population of Spotted Turtles, despite residing on protected land, are declining in size, even without the effects of road mortality. With the effects of road mortality included into the models, the population has a greater than 90% chance of reaching an extinction threshold within the next 150 years. This striking result highlights how damaging road mortality can be to turtle populations and makes it clear that preventing road mortality in other turtle populations will be a critical component of any long-term conservation plan that seeks to conserve turtle populations in developed areas. The study represents one of the first attempts to quantify the direct effect that roads have on freshwater turtle population viability. One of the implications of the study is that even populations that have persisted for long time periods and appear relatively stable from opportunistic sampling, in fact, may be on a ‘‘slow glide path’’ to extinction.

This decline may be caused by just road mortality, but turtle populations around the globe are also facing threats from poaching by humans, habitat loss and fragmentation, and increased rates of nest predation from increased prevalence of small predators (raccoons, foxes, etc.). Protecting these unique organisms in the future will require a broad approach to mitigating various threats, long-term monitoring to measure the efficacy of these practices, and constant updating of practices to achieve the best outcome possible. These results further the cause for federal listing of Spotted Turtles as an imperiled species and will hopefully spur more population research and data driven management. This study supports the growing body of evidence that freshwater turtle populations rest in a perilous position and that anthropogenic causes, such as road mortality, may have even more devastating consequences on long-term population viability than previously expected.

For more detailed information please read our recent publication in the Journal of Herpetology – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331059434_The_Effects_of_Road_Mortality_on_Small_Isolated_Turtle_Populations

A long term population analysis of a Maryland population of Spotted Turtles (Clemmys guttata)

by SWS Field Research Coordinator, Hunter Howell.

Introduction

Spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata) populations have been studied extensively throughout their range (Ernst, 1970, 1976, 1982; Ward et. al., 1976; Lovitch, 1988; Litzgus, 2000; Litzgus and Mousseau, 2004). Studies have examined the demography of populations over long periods of time in stable habitats in Canada and Pennsylvania (Ernst, 1970, 1976, 1982; Litzgus and Brooks, 2000). However no study has looked at long-term changes in a single population of C. guttata in a habitat that is under impact from development and human activity. These data are of interest, since populations of Spotted Turtles are declining, due to over-collection for the pet trade, habitat destruction and fragmentation, road mortality, predation by subsidized predators (native species who survive in part due to resources provided by humans), overgrazing by livestock, agriculture, and pollution (Ernst et al., 1994; Lovich, 1989). Because of the decline of C. guttata, long term data on population size, especially in an area altered radically by humans, are extremely important to determine if remaining populations are viable in the long-term.

My study will compare the current status of a population of C. guttata with data collected on the same population from 1982-1992. . During this time, wetlands have been created and destroyed, developments and roads have been built, and there has been an overall increase in human activity. The study will compare age and size classes, sex ratios, and overall population size to determine if this population has succeeded in remaining a viable population.

Study Species

Spotted turtles (Clemmys guttata) are small aquatic turtles recognizable by an almost completely black shell speckled with yellow dots. The species is restricted to Eastern North America where it ranges in disjunct populations from Ontario and Maine southward along the Atlantic Coastal Plain to Florida, and westward along the southern shores of the Great Lakes to Illinois (Ernst et al., 1994). Clemmys guttata utilize a variety of habitats such as freshwater ponds, vernal pools, upland forest, emergent wetlands, scrub-shrub wetlands, and forested wetlands (Lovitch, 1988; Litzgus and Brooks, 2001; Milam and Melvin, 2001). Their primary diet consists of various aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates, but they also eat plant material, carrion, and occasionally small vertebrates (Harding, 1977). Clemmys guttata become active in early spring as soon as the ice and snow melt, usually in late March to mid-April. This species appears to tolerate and prefer cooler water and air temperatures than other related turtles, often initiating activity at water temperatures as low as 2.7°C (Ernst et al., 1994). In early spring, C. guttata spend a great deal of time basking on logs, muskrat houses, and grass or sedge hummocks (Ernst et. al., 1976). Spotted turtle activity levels generally peak in May, or when mean monthly air temperatures are between 13.3 and 17.7°C, and start to decline in June, or when mean monthly air temperatures are between 17.7 and 22°C (Ernst et al., 1994). They become dormant or aestivate by late June or early July (Ernst, 1982). In Maryland, 74% of all activity occurs from March to May, inclusive (Lovitch, 1988).

Spotted turtles are a long lived species (possibly up to 110 years for females and 65 years for males; (Litzgus, 2006). They produce small clutch sizes and have very low hatchling survivorship (Ersnt, 1970). In a healthy population, low and variable survivorship in early life is compensated for by long life spans and low adult mortality (Enneson and Litzgus, 2008). This makes them prime candidates for population declines because of their low reproductive output coupled with a low percentage of hatchling survivorship. Clemmys guttata populations are currently being threatened by habitat loss, over-collection for the pet trade, road mortality, predation by subsidized predators, overgrazing by livestock, and pollution (Lovich, 1989; Ernst et al., 1994). Because of this myriad of threats, spotted turtles are now considered threatened or endangered in a significant portion of their range.

*Literature Cited available upon request

** Further details and location information kept confidential to protect the species and its habitat