Eastern Coyote on SWS trail camera (Harford County, MD)

The Eastern Coyote is one of our most controversial local wildlife species. It isn’t the return of an locally extirpated species like the Black Bear but the result of both a range extension of the Western Coyote and some small level of hybridization with both wolves and domestic dogs along the way, creating a larger version with some different adaptations. Around the time of European settlement it is believed that only their larger canine cousin the wolf and smaller foxes inhabited our region but likely not coyotes which have been more restricted to the western states and prairies. The more favorable habitat that resulted from the clearing of the landscape for farming and development as well as the removal of the wolf and cougar created an ecosystem vacuum that allowed the coyote to freely move into new areas without any fear or competition from larger predators. A local myth that perpetuates to this day is that the coyote was introduced by the Federal Government at the Aberdeen Proving Ground to control rabbits or sometimes car insurance companies to reduce deer vehicle collisions but despite these being somewhat ridiculous ideas without evidence, the facts are that Maryland actually marks one of the final two states in the east for the expansion of coyotes to reach, first seen in 1972 in three other counties, as their path was well documented moving from both the north and south, somewhat meeting in the middle, with Delaware being noted as the final state for their arrival.

WILD DOGS – Previous Article

It was a clear, moonlit night at the Susquehannock Wildlife Center. After a long evening of construction work on the facility, we huddled around a small campfire, enjoying the last remnants of warm autumn weather before winter would start to creep in. Suddenly, up the hill to the north, we heard a short howl followed by a cacophony of yips coming from a multitude of creatures. Startled by the unexpected wild chorus, we fell silent, listening intently. Our heads whipped in the opposite direction as a longer howl came from the nearby Deer Creek. We knew what we were hearing. Eastern coyotes! The sounds then started to move, converging towards each other, following the treeline to the east and then south.

We had just recently captured a photograph of an individual at our site on a trail camera, but never had we been privileged to take part in this primal communication. To us, it felt like a long lost component had returned to the landscape. With each day we gain a great appreciation of the incredible diversity of species found on this preserved piece of land that together with Maryland Department of Natural Resources we worked hard to protect. As much value as we see to a new predator finding its place in the ecosystem, our sentiment is not echoed among much of the public.

The Wolf of Ansbach, chased into a well and displayed on a gibbet (Germany. 1685)

It is astounding that an animal so beloved in its domestic form could be so hated and feared in the form of its wild cousins – wolves and coyotes. We believe that hunting of our native wildlife can have a place for both human sustenance and resource management. However, the senseless killing of our predators out of fear and misinformation is something that our society must learn to overcome. The mythology of the “big bad wolf” created through werewolf folklore, inaccurate adventure movies, and special interest groups throughout time has caused many predator populations to plummet and even disappear.

Red Wolf (in captivity)

Even today, struggling wild canines like the gray or timber wolf in certain western states and the endangered red wolf that was reintroduced in North Carolina are being persecuted because of some negative yet relatively small impacts on livestock or unfounded fear of attacks on humans. Many vocal opponents also point to their perceived large scale destruction of prized game species which in reality may just be starting to become more difficult to hunt because of a change in behavior where prey is more cautious and less likely to linger in the open.

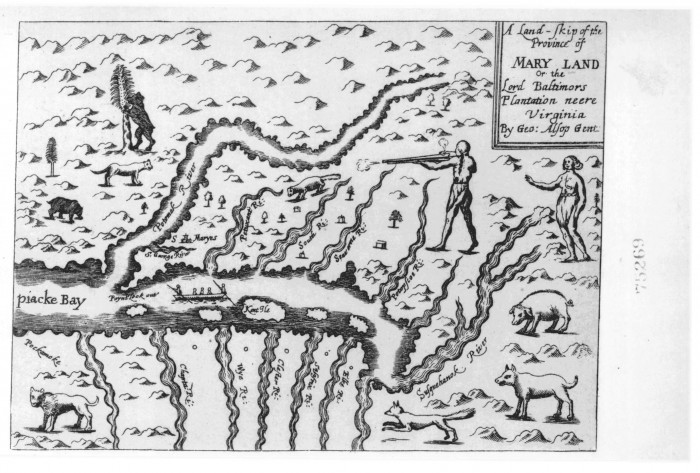

Note the now extinct wolves & cougars on the map – George Alsop, A land-Skip of the Province of Mary land, 1666

In the not too distant past, Harford County was a very different place. Up until perhaps as late as the 19th century, we still had wolves roaming the river valleys and rolling hills of our great lands bordering the Susquehanna. Unlike the trophy hunting of species like the white-tailed deer by man that often selects the strongest and most desirable prey to be harvested (large size, biggest antlers, etc), wild predators such as coyotes, if they decide to pursue a deer, usually select the youngest, injured and weak which in turn ensures that the strongest genes survive while the weaker genes are weeded out over time. Included in this diet are species like fox and raccoon that until recently lacked any significant natural predators other than humans and their cars. Rodent species are also particularly harmful to crops and spread diseases when overpopulated. Rodents such as mice, rabbits, voles, and groundhogs actually comprise the bulk of a coyote’s diet, which changes throughout the seasons with carrion, berries, and insects also being included. Predators are good for the ecosystem. In some recent studies (with the level of impact still debatable), the return of wolves out west in places like Yellowstone have shown to allow populations of many seemingly unrelated species to rebound because wolves change the behavior of their prey that otherwise overgraze critical vegetation. Keeping prey species such as deer on the move means they will be less destructive.

One powerful example of this impact is perhaps the most unlikely and close to our hearts. Other than habitat loss one of the biggest threats to Maryland’s state insect, the Baltimore Checkerspot butterfly, is that deer eat their host plant, the white turtlehead. Where populations of this plant exist or ingredients are right for them to reestablish, keeping deer on the move so they don’t overgraze all of these critical plant could actually help return this rare butterfly to portions of our landscape.

American hunters with wolf hides, Northern Rockies, circa 1920. (From PBS.org)

What happened to the wolves and what can we learn from their disappearance? For many years, bounties were set and they were hunted relentlessly from across the lower 48 states until timber wolf populations only remaining in Canada and Alaska. A small population of red wolves, found in the southeast and believed to once also inhabit Maryland, was recovered in Louisiana and eastern Texas to be put into a breeding program to protect them from extinction. A first of its kind predator reintroduction program of a species extinct in the wild started in the 1980’s and continues, although with much resistance from some hunters and livestock owners in eastern North Carolina.

Route 64. Endangered red wolves are also killed by automobiles (Tyrrell County, North Carolina)

Recently there were well over one hundred thriving red wolves in the wild recently but that number has since plummeted to less than fifty, all due to unnecessary human take of the species. There is still hope for recovery given biologists have now proven the effectiveness of their methods but even with that initial success, the program is at risk of losing federal support. This is largely due to some local opposition from private land owners, hunters, and more specifically those who resist regulations that restrict hunting of coyotes in areas where they can be confused with red wolves. The lower population of red wolves also puts the remaining packs at greater risk of hybridization with coyotes, always a major concern to maintain wolf genetic traits, than when at larger numbers. In the last decades gray wolves have begun to return in many western and Great Lakes states, also with much controversy. As soon as populations have reached a sustainable level, the wolves have been delisted and intense hunting would resume, breaking up complex social hierarchies found in the packs and putting the species back at risk as numbers would start to decline.

Western Coyote (Montana)

At the same time the more adaptable and opportunistic western coyote, originally found in the plains and western states, began to rebound and spread into new territory. As these smaller cousins of the wolf moved through Canada they interacted with the sparse populations of remaining wolves and sometimes bred out of necessity for species survival. The strongest genes of both species perpetuated, creating a new hybrid subspecies, the eastern coyote, that recent genetic studies show in the northern portions of their range there is potentially 65% western coyote, 25% wolf, and even 10% dog. These percentages vary depending on where in its range the coyote is found. Those further north have more wolf with the number decreasing as you go further south. This slightly larger, even more adaptable hybrid that some have nicknamed the “coywolf” is able to hunt in both forested area and open spaces. Indirectly, we created this new hybrid through our removal of a top predator. Over the last century the coyote has established itself across all of Maryland and most of the eastern United States. Despite stories of the contrary, they were not intentionally introduced but part of a natural migration spurred by the removal of wolves and other predators. It is here to stay so how do we coexist with it? Should we repeat our mistakes again or allow this new ecosystem that in many ways we have created to have a chance to balance itself out?

Eastern Coyote (Susquehannock Wildlife Center)

We recommend that these newcomers are given a chance. As with any wild animal, if they show signs of aggression towards humans or don’t show the typical fear response than call the proper authorities such as animal control or your local wildlife agency if a potentially rabid or dangerous individual has become too accustomed to humans. Coyotes are usually afraid of people and should flee when encountered. Even when found in suburban areas they tend to avoid people. Securing your trash and not leaving pet food outside can also reduce the potential for negative encounters. While coyotes have been known to prey upon small dogs or cats, this can be avoided in part by fencing in your property, not feeding animals outside, and not leaving pets outside for extended periods at night when coyotes are most active. We cannot allow the low probability of negative impacts outweigh the potential good that a species may provide. It is our hope that through further research and compassion that we may coexist; sharing our land with these wild dogs that are just trying to survive in a foreign land.